Restoration artists Michael Coronado and Pedro Morelos joins ‘Create Incredible’ from the Duplitech offices in LA, to talk about the growing industry of restoration, how they got into the industry, and some of the projects they are proudest of to have worked on.

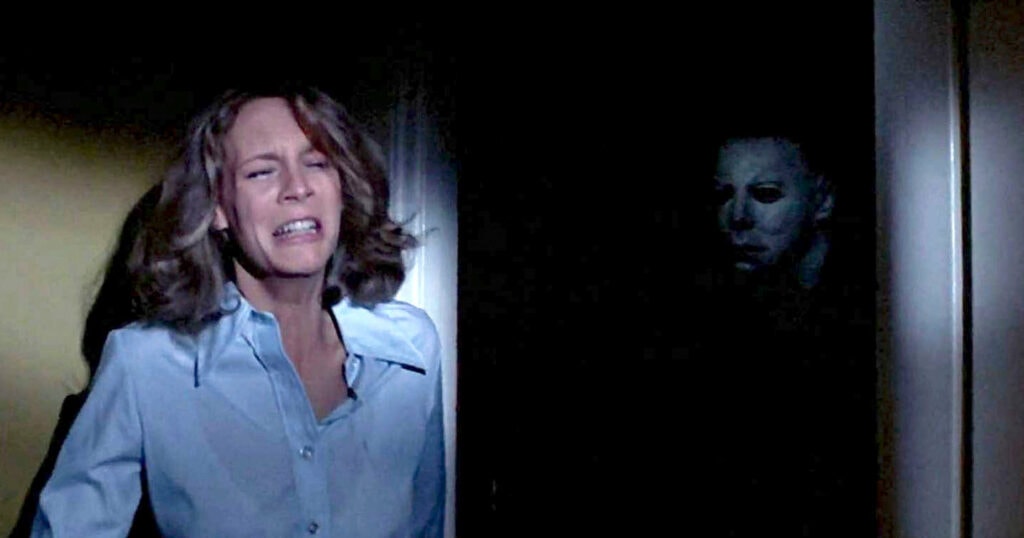

In their own words, Duplitech mostly focus on the home video market, working on the the new 4K ultra HD HDR titles that have been popular lately: ‘if you ever notice something like Halloween (1978) popping up on iTunes, then most likely our team was responsible for that restoration’

Coronado found his affinity for restoration after shadowing in a VFX studio, ironically, and despite enjoying it, it didn’t feel like a true passion. Later on, when he saw his sister remastering a James Bond film, he was eager to give it a go. Morelos, on the other hand, has touched base in most areas of post-production over the last 15 years but similarly found his place in restoration.

When asked about what drew them to restoration, Morelos answers that he started in dust busting which ‘came very natural to me; I just loved the instant gratification of removing the dirt and just knowing that that little piece of dirt was not going to be seen anymore. Or here was a shaky shot and now all of a sudden it’s stable, or it was very flickery before and now all of a sudden we have a smooth picture because of something I did’.

Coronado finds similar reward in the satisfaction of cleaning up an affected image, but also highlights the importance of ‘preserving a director’s legacy’ and that ‘you can bring something back for younger generations. I get to share some of the movies that I worked on with my kids – to see how excited they are makes it all worthwhile’.

When discussing some of their favourite projects, Coronado takes us back to working at Company3, where he worked on films like Transformers (2007), Rush Hour (1998), and Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl (2003), but focuses on his role working on the Academy Award winning The Hurt Locker (2008). There, he worked on dust busting, scratch removal, and dirt removal. ‘They wanted it to be pristine, so there were lots of hours spent zooming into quadrants on the frame making sure there was absolutely no dirt. For a newer title, it was a lot of work, and I put a lot of my own hours into it’

In the end it was all worth it: ‘I remember operations calling me and telling me ‘hey, can you check out this frame real quick? Something’s wrong – we saw a big piece of dirt there’. I thought ‘oh man, what have I missed’, and then when I checked, it was the end credits and I saw my name on the credits. It was the first time I got end credits too, I was so excited’.

One of Coronado’s restoration highlights is the 1973 Japanese animated art film Belladonna of Sadness. Now considered a cult film and famous for its vibrant and psychedelic-like imagery, it originally premiered at the Berlin Film Festival despite later being a commercial failure and bankrupting its production company, Mushi.

The film is woven together as a montage of gorgeous stills with bursts of colour and animation, with references to Art Nouveau painters such as Gustav Klimt, Odilon Redon, Alphonse Mucha, Egon Schiele and Félicien Rops. It was the first time Coronado had used Phoenix and there were no restrictions on this title, which meant they could go into a lot of detail without being worried about time constraints.

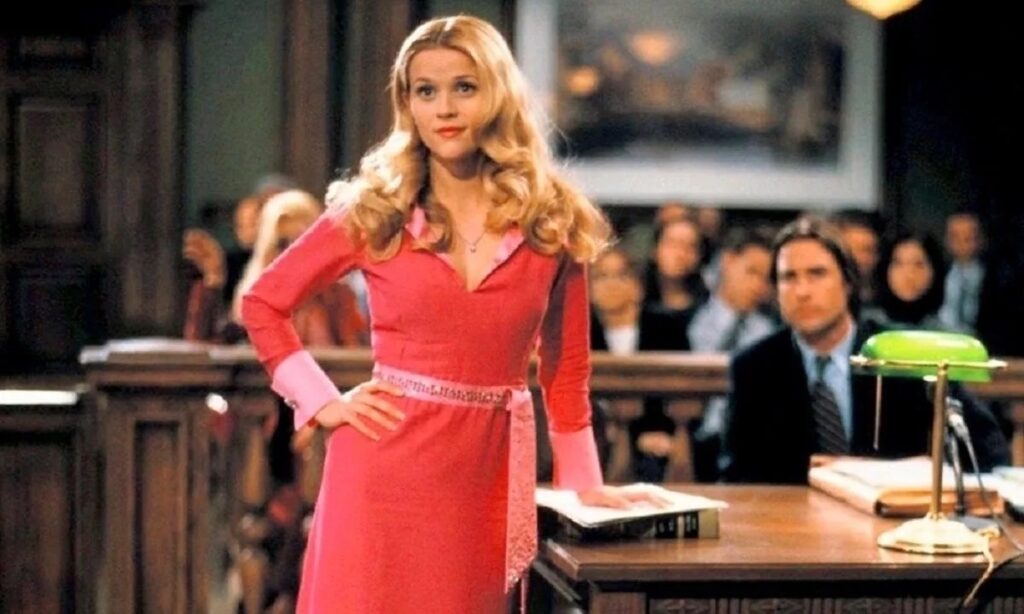

Morelos points out his time working on Marvel’s Captain America: The First Avenger (2011) as a highlight, being instrumental in changing the imagery of the 3D aesthetic through a change in sharpness. Another iconic movie that Morelos was involved in was restoring Legally Blonde (2001) starring Reese Witherspoon. He told us that the original film was ruined with lots of emulsion stains, but managed to rescue the classic chic flic with the DVO tools on Phoenix.

And if they could restore anything? Morelos wanted to get his hands on some film from Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, whereas Coronado is keen to find a copy of The Dark Crystal (1982), having lots of childhood memories attached to the film.

Whilst talking about challenges they face restoring old videos, one they highlight is having to recreate things that aren’t there. For example, when dealing with burn in markers or the real markers you might have to draw in objects and shapes that aren’t there whilst finding the best match to make it look seamless. Issues like tears, scratches, or emulsions always take a lot of extra work involved in its repair.

The duo are excited about the advent of new technology, which has gone from HD to 4K in recent years (and probably up to 8K before we realise it). They also comment on the rise of interest in restoration recently, and highlight the importance of the Filmworkz Classrooms in sharing knowledge about restoration.

They also predict restoration will be less centralised in a studio in the future, with artists more likely to be able to work from home once they have the software, spreading the reach of restoration globally. Brecht Duclercq also talks about this global transition in restoration demographics, highlighting inequalities around the world. The advancement of this technology is often driven by AI, so editing can be sped up and is more cost efficient.

They notice too that, although at the turn of the last decade filmmakers moved to digital, there seems to be more creatives returning back to film, which they celebrate because shooting on film creates gorgeous images and ‘there’s something, like a depth to the picture, that can’t be replicated with a digital camera’ (which is something Peter Doyle also touches on).

When starting out, their best advice is to just keep reaching out to companies and following up with them. In the meantime, try watching tutorials online to have a grasp of some of the tools you will be using. They also ruminate on what it takes to be a good restoration artist, answering that it requires incredible focus, as you are looking for the smallest details at all hours of the day.