Starting your own business is always a risk, but especially in India, Koushik Bhattacharya explains. This risk paid off: with his Mumbai-based restoration company, Quality Matters, Bhattacharya has gone on to restore the first ever film in India in 2003, worked with Edison’s short films that are over 100 years old, and had his work shared by the Albanian Prime Minister.

PIONEERING RESTORATION IN INDIA

During the 1990s, before founding Quality Matters, Bhattacharya was learning software development at NIIT. He later joined Hindustan Computers Limited (now HCLTech) when it merged with HP and was offered the opportunity to troubleshoot, thereby landing in post production studio VISION under the esteemed guidance of Mr. Rakesh Soni, where he learned how to edit. In India at this time – Bhattacharya explains – there was no non-linear editing, so when AVID first arrived many people didn’t know how to edit with a keyboard and mouse since they principally used analogue U-Matic and BetaCam.

What he was told about editing was that ‘there are four points: why to cut, when to cut, where to cut and how to cut. How to cut is a mechanical thing, but why, when and where is grammatical’.

With some years of experience under his belt, Bhattacharya was later asked to fix some old footage by Star TV despite at this time there being no restoration software. Instead he used the hardware tool DVNR (Digital Video Noise Reduction) but this never provided the desired results and so ultimately he had to manually correct images frame by frame.

The time taken to restore this project upset his boss Gaurav Gandhi (currently Vice President at Asia Pacific), but thanks to him, Koushik started doing extensive research on ImageProcessing algorithms that were time efficient and started using them to deliver unmatched quality in an efficient timeline, thereby meeting deadlines eventually. Without him, Quality Matters and Bhattacharya wouldn’t be where they are today, Bhattacharya credits.

Months later, news had got round that Bhattacharya had corrected the frames without any original sources and he was approached by Mrs Manju Jain the Producer to restore Mehndi Rang Layegi (1982), the Hindi romance directed by Dasari Narayana Rao and starring Jeetendra, Rekha, and Anita Raj.

Since there was still no proper software, Bhattacharya divided the film into 216,000 frames to use in Photoshop so that he could manually correct each image – ‘you have to see the film to understand the pain that we went through’. But as a result, it means that Bhattacharya restored the first ever film in India in 2003.

‘We didn’t have the proper toolkit. We didn’t have anything to restore a movie because movie defects are various – that is flicker, that has blobs, there’s patches here – but I was told I had one year to repair the film’

‘We had around 8 people painting on a daily basis, with me supervising. It took 8 months and cost 3 times what it was commissioned, but they only paid the original fee. I had to sell off my wife’s jewellery to balance the practice. It’s very difficult to do something innovative in India and before this point there was no restoration in India’.

Mehndi Rang Layegi is still being used today by broadcasters and Bhattacharya explains that ’it’s not about pride, it’s about satisfaction’ in response to knowing that his work has proved the test of time.

He explained previously what it is that draws him to restoration: ’it includes not only the mending of physical damage or deterioration of the film but also takes into account the intent of the original creator, the artistic veracity, accuracy, and completeness of the film’.

THE FUTURE OF RESTORATION IN INDIA

Although the conditions of film preservation leave much to be desired, the National Film Archive of India (NFAI) has recently announced an initiative to digitise 5,000 essential Indian films, of which 2,200 are to be restored. Bhattacharya explains that this increases every year thanks to an additional ₹300 million over 5 years, which should eventually total in 22,000 restored films. In 2016, 597 Crore INR (a Crore has a value of 10 million Indian Rupees) were contributed, and last year another 300 Crore INR.

The National Film Heritage Mission (NFHM), which is passionately led by Shivendra Singh Dungarpur, has also had a very big impact in safeguarding India’s national heritage that is embedded in celluloid. Two restorations by NFHM have recently been screened globally at festivals, the first at the Cannes Classics section with Pratidwandi (The Adversary, 1970), and the second at Venice Classics and the Toronto International Film Festival with Shatranj Ke Khilari (The Chess Players,1977), celebrating the work of esteemed Indian Golden Age director Satyajit Ray. Indian restorations are finally being enjoyed by the rest of the world.

In a conversation with Variety, NFAI chief Ravinder Bhakar said: “We wanted to showcase the importance of preservation of film and related ancillary materials, which is being done by the NFAI, a key stakeholder in the preservation of the cinematic heritage of India, through an exhibition at the Film Bazaar pavilions.”

Bhakar added: “While NFAI showcased a 35mm film reel, working 16mm projector in action, rare posters, song booklets, various formats such as VHS, Beta Tapes amongst other archival objects, the pavilion also brought focus on the work done by the NFHM. We wanted the industry to know about this mission, under which thousands of features, documentaries and shorts are digitised and will be eventually restored.”

The NFAI holds the principal objectives to trace, acquire and preserve for posterity the heritage of Indian cinema; to classify, document data and undertake research relating to films; and to act as a centre for the dissemination of film culture.

BRINGING BACK THE GHOSTS OF FILM

In 2008 people quickly started talking about the quality of the work and Bhattacharya landed their first contract with the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Science – the body who awards Oscars.

Whilst working on The Divine Miracle (1973) for the Academy, Mark Toscano (a renowned filmmaker, curator, and film preservationist based in Los Angeles who has worked at the Academy Film Archive since 2003) was so excited by what Bhattacharya could do, he asked if he could work on something older – 100 years older?

Welcomed with open arms, Bhattacharya worked on Thomas Edison’s hand held short films that were shot in 1894. Edison’s work marks the inception of cinema, with Anna Belle Serpentine Dance (a scene where a woman dances with some fabric that mimics wings) being a surprisingly ethereal and moving shot that is contained in just a few minutes.

Although famous for many inventions, like the phonograph (what would later become a record player, the rechargeable battery, and the lightbulb, Edison also provided the industry with the 24 frame rate and the motion picture camera. His studio produced mostly short films that would cover acrobatics, parades, dances, and sketches.

FILMWORKZ BROUGHT BHATTACHARYA TO THE FUTURE

Bhattacharya came across Filmworkz’s (formerly Digital Vision’s) DVO Tool’s at Broadcast India in 2007 and was the first Indian to buy the products – ‘I needed something which can do what I do for months in days. It was a big investment at the time but it was my journey to go to a further level and I can only thank Filmworkz for being so responsive to my wish’

‘Anything I needed, I would ask, and it would be passed on to the engineering team who would come back with a solution; the synergy of the development of the product with the end user kept in mind was something that I had not expected. The updates that I received with the corrections were fabulous! The best part about Filmworkz is the continuous research, development and additional features’.

Bhattacharya provides a charming analogy for restoration that draws inspiration from his everyday life: ‘I’m also a cook, so I relate restoration very closely to cooking. In cooking you have to have the right ingredients, the right spices, and the quantity of the spice needs to be very specific: too much will spoil the food. So similarly, if you want to make a delicious food, the timing and quantity of the spices needs to be perfect. That’s what Filmworkz gives you: it gives you everything that you need to make beautiful food’.

Using DVO tools since 2008 speaks volumes in itself, and Bhattacharya reveals what is his go-to… ‘DVO Dry Clean is a blessing because all the blotches that were there in the negative when it gets scanned gets cleaned like nobody’s business. It’s as if the negative never had imperfections.’

‘It is a complete package! You cannot get stuck somewhere, it has solutions for everything! If you are patient…’ There is also caution to his tale! ‘All you have to know is where to stop in restoration: like cooking, if you overcook it becomes tasteless, the food becomes spongy, or a paste. Your toolkit gives you so much liberty that we learn when to stop’.

‘People think this software is a miracle machine. It is indeed a miracle machine, but you have to give it time. If something is not happening – don’t force it, leave it for some time, go to the next clip, finish it, take a break, think about ways to re-work it, and then do it again, and you will find it is working. We work with a semi automatic process. We try not to use the fully automatic process because we believe then the film loses its originality. And restoration means you have to deliver the original – not less, not more’.

Recently, Bhattacharya has also provided upscaling services up to 24K and beyond without using AI, adapting to the ever changing demands of the media industry, which he believes is the ‘next generation’s requirement’.

BEING CONGRATULATED BY THE ALBANIAN PRIME MINISTER

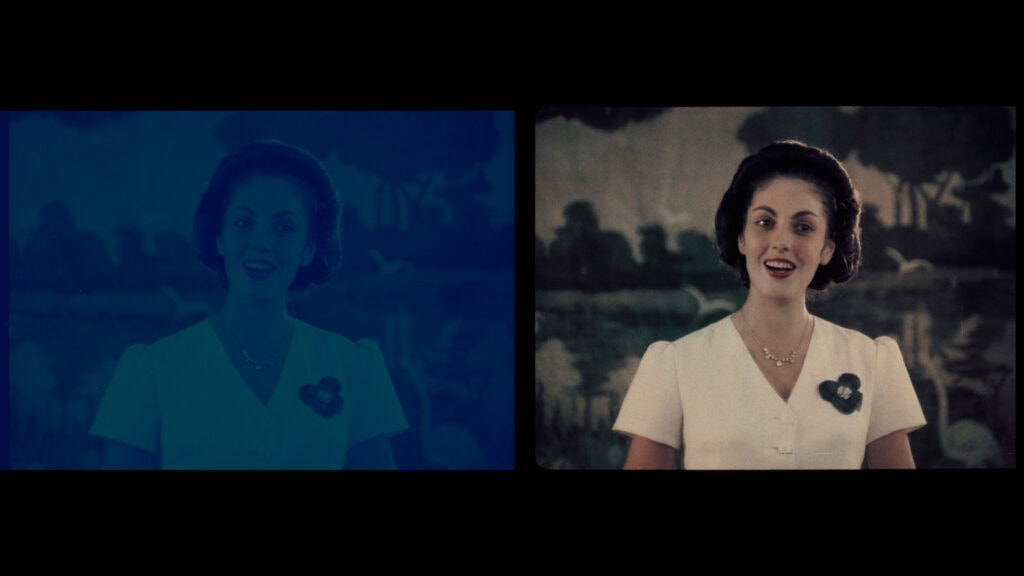

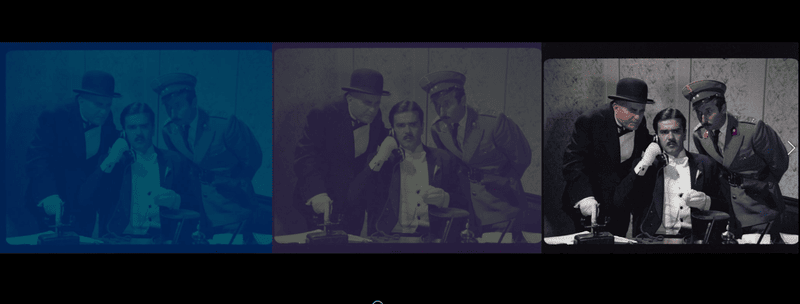

One of Bhattacharya’s proudest achievements is the restoration of the Albanian classic Koncert në Vitin 1936 (1978), which was directed by Saimir Kumbaro, and tells the story of two performers (a singer and a pianist) visiting the city of Lushnja during the time of the Albanian monarchy which shook the life of a very conservative city. In a full circle moment, the restored version of Koncert në Vitin 1936 premiered in Tirana and Libohava in 2022, the setting where it was shot decades before.

The Central State Film Archive commented at the time this restoration was ‘an added and saved asset for the Albanian audiovisual heritage. A wonderful job is being done by the team of digital restoration specialists Koushik Bhattacharya and Ritajit Raychaudhuri in Mumbai India, to restore the faded colors of the film 1936 Concert’.

In addition to the original negative copy, the Central State Archive of Albanian Film (AQSHF) preserved other memorabilia such as the literary script, the director’s script, the editing list, photographs, photo negatives, promotional materials of the work, film music scores, and their posters.

The lead actress, Margarita Xhepa, commented that ‘from the renewed film, there is a light, there is a glow if you look at it, the comparison is wonderful… We have spent half of our lives in the family, but we have spent half of our lives with the characters’.

Bringing this old gem again to the forefront of the Albanian cultural landscape was met with great acclaim, so much so that Bhattacharya’s work was shared by the Albanian Prime Minister, Edi Rama, on his facebook! He had requested his country to go and see the film online (it was on YouTube for three days).

Whilst the film may have been well received, it doesn’t reveal how difficult it was to bring this footage back to life to be watched (like any good restoration).

‘The negative had decayed beyond repair; the chemist in Albania told me the negative was smelling and was sticky, the red color channel was lost, so the footage had turned blue, she could not see any other colour. I asked her nonetheless to send me a reel, and I worked on it for a week and nothing was coming out. I gave it to my grading team in Bombay – a very film dominant city because this is where Bollywood exists – and all the big colorists tried but couldn’t fix it’

‘Then I recalled a previous project in 2010 where I used software called combustion which could fix colors, and I had to battle with balancing the colors…it took me 3 and a half months just to do the color channel restoration’.